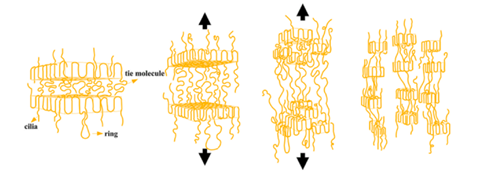

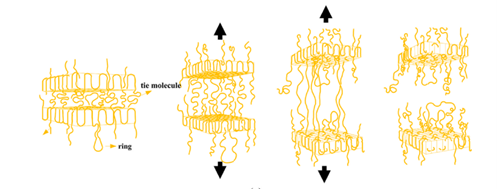

At the microscopic scale, polyethylene, as a semi-crystalline polymer, has a microstructure composed of crystalline lamellae and amorphous chains. It is generally assumed that polymer chains in the crystalline regions are folded and aligned side by side. In the context of polymer failure, the so-called tie molecules—polymer chains that connect crystalline and amorphous regions—play a critical role. These tie molecules act as reinforcing elements and stretch under high stress until they

can no longer bear the load. At this point, the crystalline layers break down into smaller fragments, resulting in ductile failure (Figure 1).

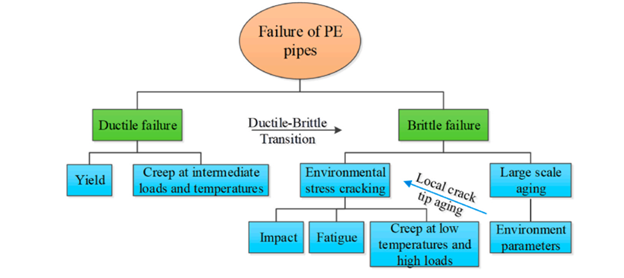

At the macroscopic level, ductile failure is characterized by extensive material flow around the damaged area and typically occurs under higher stress or shorter timeframes. This failure mechanism is associated with viscoelastic behavior, especially in creep-induced rupture, where the time to ductile failure depends on the creep rate.

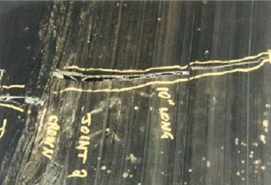

As shown in Figure 2, due to material heterogeneity, excessive internal pressure in polyethylene pipes leads to significant deformation and localized soft damage. Similarly, large external loads—such as third-party damage or mechanical

excavation—can also cause ductile failure.

Figure 3 illustrates how external factors like ground settlement or mechanical digging can generate high stress and lead to ductile failure in polyethylene pipes.

Compared to ductile failure, brittle failure in polyethylene materials typically occurs under lower stress levels. Microscopically, tie molecules gradually loosen and detach from the crystalline regions over time. This increases stress concentration on the few remaining tie molecules. As these molecules are continuously pulled out and cracks propagate, the material ultimately undergoes brittle failure (Figure 4).

At the macroscopic level, brittle failure is associated with crack growth, known as Slow Crack Growth (SCG), which occurs over a longer period than ductile deformation. This failure process is directly linked to the formation of craze structures—microvoids or defects that lead to crack initiation and propagation. Eventually, when these cracks penetrate the pipe wall, brittle failure occurs. It is worth noting that polymer chain scission plays a relatively minor role in the breakdown of these structures.

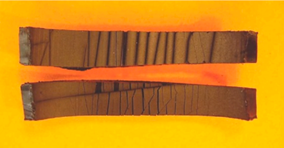

Figure 5 shows the typical morphology of brittle failure in HDPE pipes. Minimal plastic deformation and extended time to failure are key characteristics of brittle failure, which takes significantly longer than ductile failure.

In general, ductile and brittle failures can occur simultaneously, and the final failure mode depends on which process dominates under specific conditions (e.g., environment, oxygen presence, external loads, temperature, and defects). For example, when researchers scratched the surface of PE pipes and subjected them to burst pressure, brittle failure occurred rather than ductile. Similarly, brittle failure was observed in tensile tests on pre-cracked PE pipe samples.

Environmental factors such as thermal-oxidative aging, photo-oxidative aging, chemical exposure, and biological degradation accelerate the consumption of antioxidants. This leads to crosslinking, molecular chain scission, and ultimately the degradation of polyethylene pipes. For instance, thermal-oxidative aging is typically considered a free radical chain reaction with autocatalytic characteristics, involving initiation, propagation, and termination stages.

Currently, the oldest polyethylene pipes in China have been in successful operation for over 40 years, and their usage continues to grow. Stress-independent brittle failure has only been observed under laboratory conditions during accelerated artificial aging (Figure 6).

In this case, non-uniform aging is clearly visible, with more severe degradation on the outer surface of the pipe compared to the inner surface. This is expected in pipe sections placed in ovens, where higher temperature and oxygen concentration on the outer surface lead to phenomena such as chain scission, microcracks, and macroscopic fractures. Additionally, aging at the tip of localized cracks has been reported to influence the SCG process.

Ultimately, the final failure mode of aged polyethylene pipes manifests as large-scale brittle behavior. In reality, polyethylene pipe failure results from a combination of ductile and brittle mechanisms. These processes occur simultaneously, and

the dominant failure mode depends on material integrity, environmental parameters, and mechanical conditions. Therefore, polyethylene pipe failure under various loading and environmental conditions can be summarized as shown in Figure 7.

Reference: S. Zha, H-q. Lan, H. Huang, Review on lifetime predictions of polyethylene pipes: Limitations and trends, International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping 198 (2022) 104663.